Statistics in context

What the evidence below shows is that there is a significant disproportion of people from certain BME groups being affected by police practices like stop and search, being arrested, being sentenced and imprisoned. What it is important to note is that this does not mean that certain people or groups are more criminally-inclined than others, but, rather, that there is a whole process at work – of bad housing, school exclusion, poverty, precarious employment – which stacks the odds against some people.

There is also racism entrenched in the criminal justice system. Now, and after decades of campaigning against injustice by black and human rights groups, it is being acknowledged, even by some very senior police chiefs, that the criminal justice system, especially the police, needs to address the issue.

For there is a perception (or call it prejudice, stereotype, stigmatisation) within rank-and-file police, as in much of society and compounded by parts of the media, that certain groups present a problem and therefore require particular surveillance and treatment. This could be because they look ‘foreign’, do not have regular work, hang out on the streets, frequent certain places, listen to particular music, live in certain areas or estates. They have been constructed by society as a ‘social problem’.

And the institutions of the criminal justice system: police forces, prosecuting agencies, magistrates, judges, QCs etc are not diverse i.e. do not reflect the total population. The workers within them will be unlikely to have been part of the same lived racial and class experience as defendants. For example, in 2019 92.6% of judges in Great Britain were white and 7.4% were from a BAME background. And in 2020, 92.7% of police officers were white and 7.3% were from BAME backgrounds.

But the context is larger than institutions being ‘white’ and individuals being prejudiced. We live in what is known as a neoliberal society – as opposed to a social welfare society. Services that used to be there to help and protect young people and marginalised groups in particular have been axed. And it is effectively left to the police now to deal with the fall-out in society.

The criminal justice system

People from black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) communities are over-represented at almost all stages of the criminal justice process, disproportionately targeted by the police, more likely to be imprisoned and more likely to be imprisoned for longer than white people.

Labour MP David Lammy’s research (‘the Lammy Review’) into racial disproportionality in the Criminal Justice system in 2017 revealed, among other things, that ‘a majority of BAME people (51%) believe the criminal justice system discriminates against particular groups and individuals, compared with 35% of the British-born white population. This lack of trust starts with policing, but has ripple effects throughout the system, from plea decisions to behaviour in prisons’.

POLICING

Stop and search

People with BAME heritage are more likely to be stopped-and-searched than white British people. There are three key powers the police can invoke to stop and search an individual that emerge in different statutes.

- Section 1 of the Policing and Criminal Evidence (PACE) Act 1984 (and associated legislation including section 23 of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971) allows the police to stop and search someone they think is carrying items like stolen property or drugs.

- Section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order (CJPO) Act 1994 allows the police to stop and search someone within an authorised area to prevent violence involving weapons.[1]

- Section 44/47A of the Terrorism Act (TACT) 2000 allows the police to stop and search someone if they suspect an act of terrorism is about to take place (after authorisation by a senior officer).

Between April 2019 and March 2020, the government data found there were:

- 54 stop and searches for every 1,000 black people compared with just 6 for every 1,000 white people. However, the figure for black people is likely to be a gross underrepresentation. For black people who do not identify or have been misidentified as either black Caribbean or black African, and labelled ‘black other’ their stop and search rate was 157 for every 1,000 black people.

- 16 stop and searches for every 1,000 people with a mixed ethnicity and 15 for every 1,000 Asian people, compared to white people

In 2021 according to Stopwatch, black people were nine times more likely to be stopped and searched under section 1 of PACE for suspected drug possession despite using drugs at a lower rate than white people. In 2011, black people were six times more likely to searched for drugs, showing a marked increase over a ten-year period.

Between 2019 and 2020, the government data found:

- 6,396 section 60 stop and searches involved White people (35.7% of all section 60 stops)

- 4,480 section 60 stop and searches involved Black people (25.0% of all section 60 stops)

The year before, 2018-2019, the police stopped and searched 4,858 black people and 2,669 of white people. At the time, that meant a black person was 47 times more likely to be stopped and searched under Section 60 than a white person (260 searches per 100,000 population for black people, compared to 5.5 per 100,000 population for white people).

London in focus

It is important to note that in London, the Metropolitan Police routinely conduct more stop and searches than anywhere else in England and Wales. For example, in the year 2019-2020 almost half (49%) of all stop and searches occurred in the capital, and there were 34 stop and searches for every 1,000 people in London, compared with 6 per 1,000 people in the rest of England and Wales. Furthermore, the stop and search rate for black people in London is significantly higher than the average across the rest of England and Wales, with 71 stop and searches occurring for every 1,000 black people, compared with 28 per 1,000 black people in the rest of England and Wales.

However, on average across England and Wales between 2009/10 and 2018/19, black people were six times more likely to be stopped and searched than white people, whilst Asian and mixed-ethnic heritage were twice as likely to be stopped and searched than white people.

Stop and search practices are largely ineffective. Between 2020 and 2021, the Home Office found in 77% of stop and searches, across England and Wales, the outcome was recorded as needing ‘no further action’.

There were no stop and searches under section 47A of TACT between 2019 and 2021. Unlike the year 2017-2018, where there were 149 stop and searches under section 47A of TACT.

Arrests

There were 646,292 arrests carried out by territorial police forces in England and Wales between 2020 and 2021. The Metropolitan Police accounted for the greatest number of these arrests (17% of total arrests). Following the pattern of previous years, persons who identify as black or black British were arrested at a rate over 3 times higher than those who identified themselves as white; mixed and ‘other’ ethnicities were arrested at a rate around 2 times higher, and people who identified as Asian or Asian British were arrested at a rate 1.2 times higher.

In London, 52% of people arrested by the Metropolitan Police were from the Asian, black, mixed and ‘other’ ethnic groups combined – the highest percentage out of all police force areas across England and Wales.

According to Joint Enterprise – Not Guilty by Association (JENGbA), the joint enterprise doctrine (whereby people can be arrested and convicted of an offence, despite not having committed it, if they knew about it or are seen to have encouraged its act) is disproportionately used against BAME communities. Of around 500 prisoners JENGbA is currently working with, around 80 per cent are from BAME communities.

Offences

Black, Asian and minority ethnic people are more likely to be arrested for drug offences compared to white people. In 2016, the Ministry of Justice (according to the Lammy review) found that for drug offences, the odds of receiving a prison sentence were around 240% higher for BAME offenders, compared to white offenders. In 2018, the government reported that just 8% of white suspects were arrested for drug offences compared to 19% of black, 15% of Asian, 15% of mixed ethnicity and 12% of Chinese or other ethnicity suspects.

Of those sentenced at court of possession of weapon offences in 2018, black defendants had the highest custody rate (i.e. the percentage of offenders given an immediate custodial sentence, out of all offenders being sentenced in court for indictable offences) at 42%, whereas the custody rate for all other ethnic groups varied between 31% and 37%.

Prosecutions

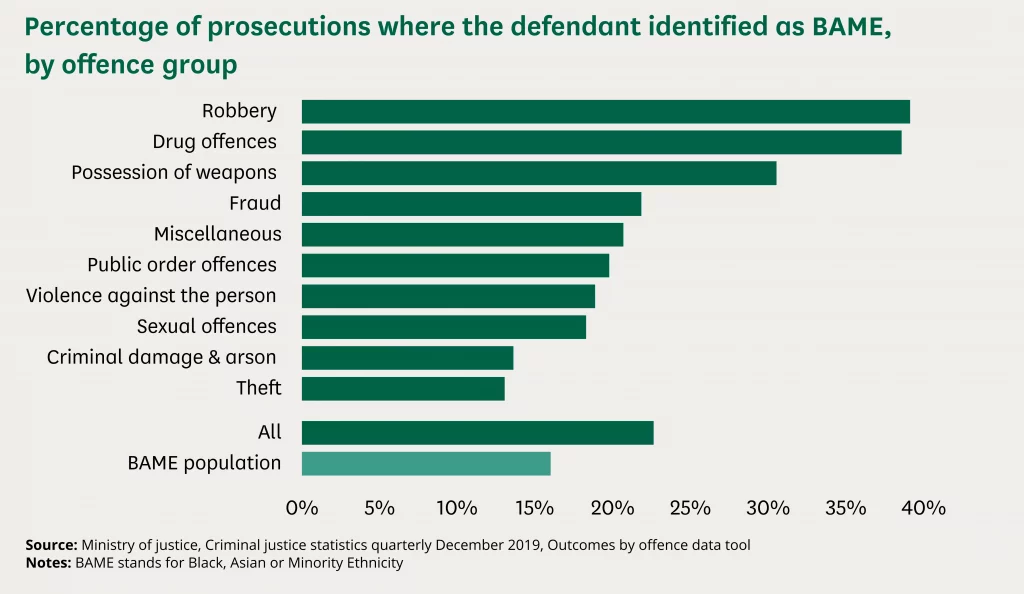

In 2019, the Ministry of Justice found that BAME defendants were more over-represented in relation to three particular offences prosecutions for robbery (39%), drug offences (39%), and possession of weapons (31%).

Sentencing

Certain black, Asian and minority ethnic people are more likely than white people to be sentenced to immediate custody for offences which can be tried in the Crown Court (indictable offences). In 2018, according to government statistics, 37% of Asian and Chinese people convicted for indictable offences were sentenced to immediate custody, compared to 35% of black people, 34% of those from a mixed ethnic background and 33% of white people.

Overall, the average custodial sentence length (ACSL) has been rising in general in recent years, but the rise has been steeper for BAME offenders. For example, between 2009 and 2019 the ASCL rose by 4.9 months for white offenders and by 8.0 months for BAME offenders, almost double the amount of time.

Prison

Despite making up just 14% of the general population, BAME prisoners are significantly over-represented in the prison system, with approximately 27% of the overall prison population from a BAME background in 2020.

In 2018, the adult prison population was comprised of 73% white, 13% black, 8% Asian, 5% of mixed ethnicity and 1% from other ethnic groups. However, black people according to the last census in 2011, make-up just 3.3% of the general population, meaning they are nearly four times as likely to end up in the prison population.

According to the Equality and Human Rights Commission, there is greater disproportionality in the number of black people in prisons in the UK than in the United States.

Young people in custody

David Lammy MP, highlighted in his 2017 report into the criminal justice system that whilst Youth Offender Institutions (YOIs) were established by the 1998 Crime and Disorder Act, with a view to reducing youth offending and reoffending and have been largely successful in fulfilling that remit. Yet despite this fall in the overall numbers, the BAME proportion on each of those measures has been rising significantly.

Over the last ten years:

- The BAME proportion of young people offending for the first time rose from 11% year ending March 2006 to 19% year ending March 2016

- The BAME proportion of young people reoffending rose from 11% year ending March 2006 to 19% year ending March 2016

- The BAME proportion of youth prisoners has risen from 25% to 41% in the decade 2006-2016

In 2020, 32% of children in prison were black despite black prisoners accounting for only 13% of the entire prison population.

Foreign national prisoners

Foreign nationals are overrepresented in the criminal justice system. In 1995, there were 4,089 foreign national prisoners in England and Wales, and just under 10,000 in 2021. In total, foreign nationals made up 13% of the prison population and come from 176 different countries.

Foreign nationals from Europe accounted for the greatest proportion of all foreign nationals within the prison population (47% from EEA countries and a further 12% from non-EEA European countries). Those from Africa (17%) and Asia (12%) contributed the second and third largest proportion respectively. Prisoners originating from the EEA made up just under 5% of the total prison population.

[1] From April 2019, under a pilot scheme agreed by the Home Secretary, some changes were made to the conditions under which a section 60 search could be carried out. The changes included:

- Reducing the rank of authorising officer from senior officer to inspector;

- Relaxing the grounds from a reasonable belief that serious violence will take place to a belief that it may take place;

- Increasing the length of time the Section 60 order can be in place from 15 to 24 hours;

- Reducing the rank of officer who can extend the order for a further 24 hours from senior officer to superintendent;

- Removing the requirement for forces to communicate to local communities in advance, where practicable, where a Section 60 order is in place.